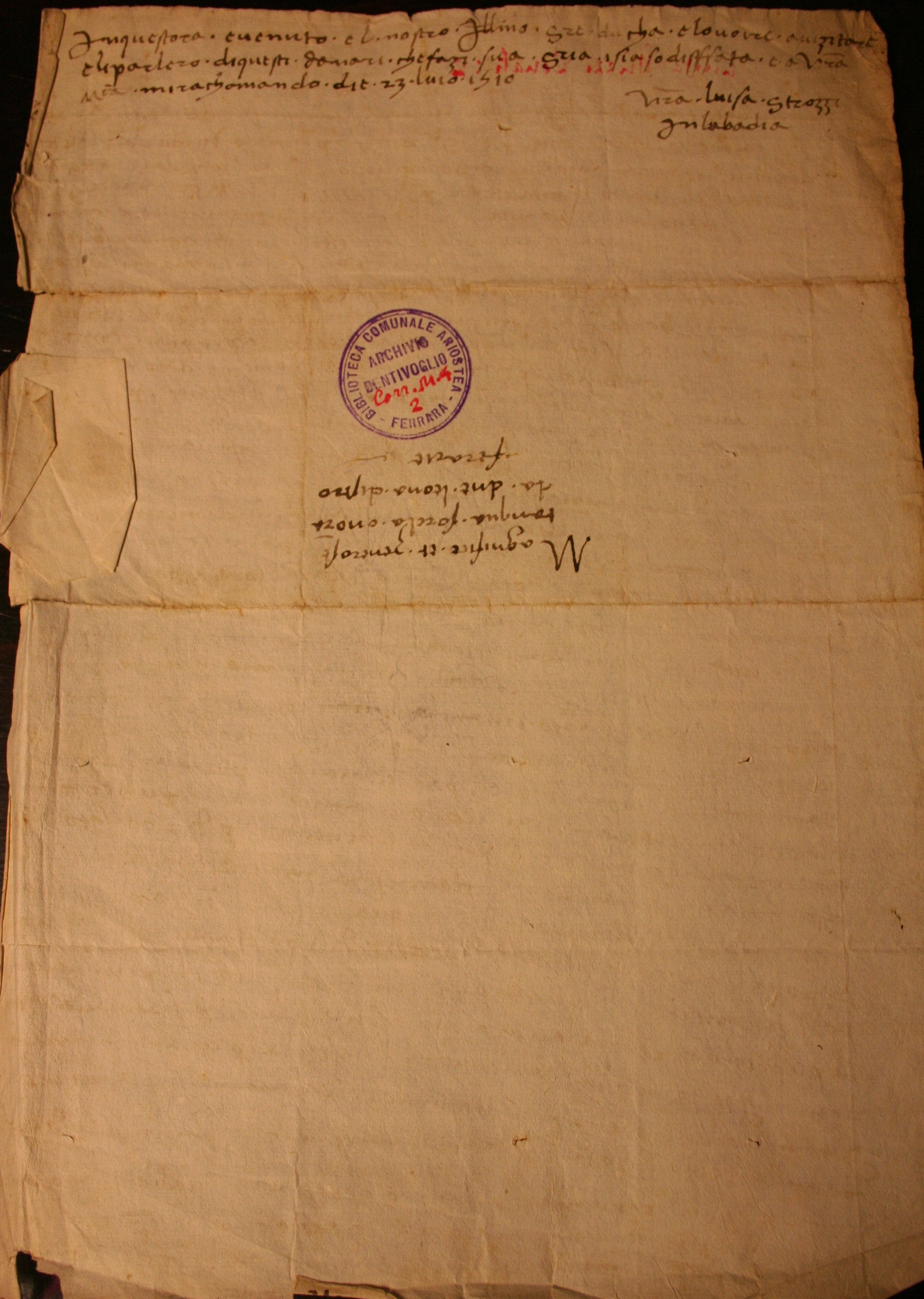

To Leona Strozzi in Ferrara, 23 July 1510

Archivio di Stato, Ferrara, Archivio Bentivoglio, Lettere Sciolte, Mazzo 4, fol. 2r-v

2 recto

Magnificha e charissima sorella, ↓Leona Strozzi was a

female relative of Luisa with whom, as her letter suggests, Luisa shared a close and

affectionate bond.

Leona was the daughter of Messer Roberto di Nanni Strozzi. See note below.

ne dì pasati vi

scrissi e deti la letera a me

↓

A partial fragment of the letter appears to be missing in

the top right-hand corner and with it the possibility of two letters which make a

certain transcription of

the last word of the line and the first word of the subsequent line not possible.

sozio de’ Buoli, el quale è qui per el Signore Ducha. ↓

The son of Ercole d'Este and Eleonora d'Aragona,

Alfonso d'Este (1476-1534) became Duke of Ferrara at the death of his father in June

1510. Luisa's reference here implies her

long association with the court, and which lasted right up until her death, as this

letter demonstrates.

Pregalo vi mandasi la letera.

Di poi vene chosta u’ mio amicho, nostro Vizio, ↓

The informally named Vizio was a Strozzi friend who

also must have also served as a trusted bearer and messenger for Luisa, given the

personal task with which he is here delegated to

undertake on her behalf.

el quale lo mandai a Vostra Magnificenza

a savere se avi auuto la mia letera per intendere di Vostra Magnificenza e per avere risposta, ↓

Luisa's letters are

populated with informal references to carriers and messengers. A trusted messenger

could furnish the otherwise capricious

process of delivering letters and goods with certainty.

e mi dize che non avi auuta mia letera, ↓

The epistolary accounting to which Luisa submits her letter to Leona Strozzi

provides an insight into the anxiety that could accompany the dispatch and reception

of correspondence. The slowness and potential for laziness or negligence on the

part of bearers or carriers, and the threat of interception, meant that the letter's

discourse was one that could be interrupted, scrambled or lost, and hence Luisa's

anxiety here.

e che

fra pochi zorni

↓

Various words employed by Luisa in her

letter-writing are overlaid by the Venetian dialect, of which the Ferrarese dialect

is very similar. This linguistic

slippage resulted in other orthographic renditions, such as the example underscored

here of the use of 'zorni'

for 'giorni'. The complex pattern of exile and expatriation created a hybrid

vernacular in which Tuscan intersected with Venetian and Ferrarese dialects,

reflecting Luisa's migration from Tuscany as an adolescent girl to the regions of

the

Veneto and the Emilia-Romagna, where she would live for the remainder of her life.

The overlay of Venetian and Ferrarese in the example from the letter is important

for

the evidence it begins to offer regarding the linguistic variations, perhaps even

mutilations, to which women who left their natal cities in Renaissance and early modern

Italy could be subjected.

el verà a Ferara.

↓

The principality of

Ferrara, located in the region of Emilia and on the Po River. In 1329 the Papacy recognised

the Este Signoria,

and the Este family were invested with the rule of the city. Their dominion over Ferrara

was long and powerful,

lasting until 1597. Ferrara was an important city of long-term settlement for various

exiled nuclei of the Florentine Strozzi,

of which the branch to descend from Palla Strozzi is a notable example. The origin

of the first

Ferrarese branch of the Florentine Strozzi had its seed in the appeal noble foreigners

exerted for the Estense court.

These Strozzi were courtiers, dependant upon lordly favour and determined to wholly

integrate themselves

into the Ferrarese aristocracy. This indissoluble binding to the Este, whom they served

in various distinguished capacities,

ensured the favour and protection of the princes, and a seamless integration into

the Ferrarese courtly elite. Dividing his time between his

business interests in Venice and Ferrara, it is probable that the establishment of

Giovanfrancesco Strozzi’s

household in Ferrara in 1453 brought the nineteen-year-old Luisa to the court city:

a strategic choice, no doubt, given the presence of

his kinsmen. Importantly, this matrix of kinship networks and ultra-municipal connections

was also exploited by the Strozzi widow.

Sichè chugina mia charissima, o diliberato iscrivervi che non o persona abia

più fede e porti più amore che in la Vostra Magnificenza e savi, che vi mandai lo stromen-

to ↓

It is plausible that Luisa refers to a legal instrument that she

was to entrust to Leona, and which was related to a rental and property dispute about

which the Strozzi widow provides some

of the particulars below.

to che mi fe fare

↓

Luisa's insertion of a maniscule in this section of the text directs attention to

the involvement of the duke in the

property transaction and rental arrangements now under dispute.

e lo Illustrissimo Signore Ducha

Erchole,

↓

Ercole I d'Este (1431-1505) was the second

duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio from 1471. The establishment in the early 1470s

of a

close political alliance between Ferrara and Naples, secured by the marriage of King

Ferdinand I’s

daughter Eleonora of Aragon with the duke Ercole was a watershed for the Strozzi.

It inaugurated

a pivotal patronage relationship for the family lines in Ferrara. Luisa's correspondence

reveals that

even the serious needs or claims of women in this big and dispersed lineage were the

concern of the duke and duchess

of Ferrara.

Illustrissima prezezia

↓

Luisa writes 'prezezia' for

'presenza' here.

di Messer Za’Lucho

↓

The identity of this person is obscure.

fra el chonte Borso Chalchagnini ↓

The son of

Marietta Strozzi, Luisa's niece, and Teofilo Calcagnini (1441-1488). Borso's father

Teofilo became a favoured courtier of Borso and

Ercole d'Este and an intimate of the court. Various letters of Luisa Strozzi suggest

that, through her niece Marietta, the Strozzi widow

was able to exert a modicum of influence over Teofilo himself for personal and familial

gain. The precise nature of the relationship between

Luisa and Borso is unclear, though his presence in the property transaction under

dispute suggests the maintenance of her connection to the

Calcagnini men and this informal family network long after Teofilo's death.

e mi de una posisione chomperai a Belob[...]

↓

A fold and partial tear

in the folio obscures the last two or, possibly, three letters of the last word of

the line: a geographical location which I am unable to identify.

da Madona Marietta ↓

'Madonna' was a personal

title used for married women. It is spelt 'Mona' in the short form. Marietta Strozzi

(born c. 1448) was the niece of Luisa Strozzi: the

daughter of Lorenzo di Palla Strozzi, the brother of Luisa's husband, Giovanfrancesco

Strozzi. She had lived as a ward with

Giovanfrancesco following the death of her parents. Marietta's marriage to Teofilo

Calcagnini provided Luisa with an important and strategic familial connection at the

Este court.

e suo fiolo chon pati che la volevano apropiare e mi paga-

vono de’ uso ogni ano 5 perzento, ↓

Luisa's use of 'perzento' for 'percento' is a further example

of dialect variation in her letter-writing. The pattern of variation detected in the

regional dialectology of some words involves

the letters: 'c', 'g' and 's', and which Luisa supplemented with the letter 'z'.

e parechi ani no’m’ano dato usi nisu’

in [...]-

↓

A fold and partial tear in the folio obscures the last one or two words of the line,

and including the

first word of the subsequent line.

do che o d’avere [dicha vi dale] e usi denari 700: zoè ↓

'zoè' for 'cioè'

duchati setezento

↓

Luisa's calculations in the text offer a further example of the hybrid vernacular

which is dispersed throughout her letter-writing: in this instance, 'setezento' for

'settecento'. It appears

from the widow's calculations and her awareness of the market values of property and

of rates of interest that

Luisa had a significant level of competence in numeracy. However, the precise details

of the property and rental dispute

about which Luisa anxiously writes to Leona here are somewhat obscure. It would appear

that rental income owed to the widow

was long outstanding. Such disputes, particularly with her adult sons, were a major

preoccupation of Luisa's letters; though this particular

conflict is especially interesting for the evidence it provides regarding the intricate

entanglement of the court in the

widow's property affairs.

e perchè so’vechia

↓

At the time of writing, Luisa was seventy-six years old. She died

three months following this letter in October. In referring to her old age, the letter

offers a rare opportunity to see how

Luisa perceived her own body in its gradual decline. Moreover, the reference coveys

a degree of Luisa's anxiety and sense of

vulnerability regarding the way in which aging prevented her from travelling and from

protecting her property, as the letter proceeds to detail.

e per queste ghuere ↓

Luisa refers to the conflicts of the War of

the League of Cambrai, a major conflict in the Italian Wars fought from 1508 to 1516

between France, the Papal States and the Republic of Venice, and precipitated by the

formation of a powerful anti-Venetian alliance secretly formed in 1508 by Pope Julius

II, Hapsburg Emperor Maximilian I, France, Spain, and the cities of Ferrara and

Mantua. The context of warfare throughout the peninsula is evident in Luisa's

reluctance to travel through the countryside to Ferrara, hinting at the dangers

resulting from the passage of Franco-Imperial forces against Venice. A letter from

Luisa's daughter-in-law Lucia, writing to her husband, Carlo Strozzi, two months

after the letter here, illustrates the perils explicitly. Lucia reports on the

plundering of the wine, furniture, grain, even the chickens and ducks, and, intriguingly,

the

destruction of her writings and the household account book stored in the farmhouse

by

Franco-Prussian soldiers. The letter, dated 23 August, is in the Archivio di Stato,

Ferrara, Archivio Bentivoglio, Lettere Sciolte, Mazzo 4. An extract of Lucia's letter

is published in

[Cecil H. Clough, ‘The Archivio Bentivoglio in Ferrara’, 'Renaissance

News', Vol. 18, No. 1 (1965), 12-19 (pp. 15-16)]

e zia

↓

Luisa writes 'zia' for 'già.

per

non esere chosta elo Illustrissimo Signore Ducha non o voluto

venire chosta. Sichè chugina mia questi danari no' so' dia dota e li vo lascia-

re per l’anima mia una parte dove va el mio chorpo a Padova ale mo-

nache di Santa Maria di Betale, ↓

The church and monastery of Santa Maria di Betlemme in Prato della Valle, Padua, in

which Luisa specified that

she wished to be buried. The church and monastery closed in the wake of the

Napoleonic anti-ecclesiastical decrees and was completely demolished in the early

nineteenth century. Importantly, it was generously patronised by Luisa's father-in-law,

Palla Strozzi

and, later, his son Onofrio Strozzi. The monastery complex abutted the house built

by

Palla in Padua in 1434, where he found refuge following his exile from Florence, and

where it is known that Luisa and her small children lived until 1453.

che la

prima che v'ando fu mia Madona sorella di

Messer Nani, padre di Messer Ruberto vostro e ave nome Madona Marietta ↓

Importantly, Santa Maria di Betlemme was where Luisa's father-in-law, Palla, and his

first wife,

Marietta, and, presumably, Luisa’s husband Giovanfrancesco were buried. In this section

of her

letter, Luisa inserts herself into the Strozzi's burial lineage at Santa Maria di

Betlemme, tracing its beginnings to Marietta Strozzi, the sister of Messer Giovanni

(Nanni) di Carlo Strozzi [d. 1427],

also mentioned in the letter. The burial lineage of these Strozzi illustrates the

centrality of the Ferrarese connection.

Nanni was a Ferrarese general of Florentine descent who was one of the most

highly respected commanders of the anti-Viscontean coalition. Inaugurating the most

important

Ferrarese branch of the Strozzi family, Nanni's distinguished standing in Ferrara

facilitated a seamless

integration into the court nobility that was exploited by numerous branches of the

Strozzi. Luisa's genealogy also includes

Roberto Strozzi. Along with his brothers, Niccolò, Lorenzo, and

Tito Vespasiano, Roberto Strozzi succeeded his father, Nanni, in penetrating the

restricted entourage of the Este princes, and consolidating at every level his place

in Estense society. Roberto was assigned the important territorial office of General

Commissariat of Romagna.

[Lorenzo Fabbri, ‘Da Firenze a Ferrara. Gli Strozzi tra Casa

d’Este e Antichi Legami di Sangue’, in 'Alla Corte degli Estensi. Filosofia, arte

e

cultura a Ferrara nei secoli XV e XVI. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi',

ed.

Marco Bertozzi (Ferrara: Università di Ferrara, 1994), pp. 91-108 (p. 95)]

e per tutti li atri nostri, ↓

In this final act of remembrance, Luisa's burial choice

reflects her particular devotion to the Strozzi and the perpetuation of her memory

among both their dead and

living. Luisa died on 31 October 1510. Whether her wishes to be buried in Santa Maria

di Betlemme were granted is unknown.

perchè i'o fato el mio testamento e

lascio la mia dota

per terzo a 2 mia fioli e a mio nivo fiolo ↓

Luisa refers here to her grandson, Roberto, whom she

affectionately called Robertino, and to whom she allocated a portion of her dowry

as a bequest. Robertino was the son of

Roberto Strozzi and Laudomia Acciaiuoli. Laudomia was from a once first-rank Florentine

political family whose

political pedigree had since been tainted by exile.

dela buona memoria de

Ru- berto. ↓

Roberto Strozzi was the eldest son of Luisa and

Giovanfrancesco Strozzi. Born in Ferrara in 1465, Roberto was educated as a

page in the court of Ercole d’Este I where, as was customary within the courtly

environment, he could cultivate military skills together with more peaceabale

achievements. Military prowess could provide a means of social mobility. When Roberto

was recruited into the military service of Venice is unclear, but he served the

Republic until his death at thirty as a mercenary captain in the battle of Taro in

1495, fighting as part of the Italian League led by Venice against Charles VIII in

1495.

Ma questi sono danari chi’ i’o ghuadagniati in chorte di mia provigio- ne in diezi ani li steti; ↓

In outlining the conditions

of her commemorative bequest, Luisa makes explicit her salaried appointment at the

Este court and her access to personal sources of income. At the request of the Este

Signoria in 1480, the Strozzi widow was requested to come to Ferrara to stay at court

with

the Duchess Eleonora and look after her two daughters Isabella and Beatrice d'Este.

Luisa's appointment as governess of the Este princesses lasted from 1480 to 1490,

though she remained a permanent member of the court and the recipient, therefore,

of

its continuing patronage and support until her death.

sichè chugina

mia charissima, vi dicho che sian' tutti mortali. Se piazesi a Dio i manchasi innazi, io venisi chosti. Tenete que-

sta mia letera per testimonanza che la mita voio dare ale suore sov-

radite che li investicha in tere in Padovana che sepre duri ↓

The letter indicates here that

Luisa was capable of giving financial, specifically landed investment, advice. The

reiteration

of Luisa's instructions in her testament to Leona, that the bequest to the monastery

be invested in land

in Padua, reveals a sensible and calculated investment maneuver on the part of the

Strozzi widow regarding

the life span of her bequest to the Augustinian nuns.

e abino qu- ela entrata, ↓

The maintenance of the monastery and the support of its

community of Augustinian nuns were the focus of Luisa Strozzi’s gift-giving and

commemorative bequests; and to which activities she refers in the letters written

during the last decade of her life, from 1500 to 1510.

e l’atra mita vo' dare a

mio nivodo Ruberto,

↓

Robertino di Roberto Strozzi. See note above.

ch’è a

Firenze e li vo rischuotere una posisione fu venduta per denari 200 soto la ba-

dia ↓

The epistolary sources are unclear as to which ‘Badia’ Luisa here refers, and on which

see

the note below.

qui a preso da una Madona Franzescha,

↓

'Franzescha' for

'Francesca'. The identity of the woman mentioned in the letter remains obscure.

ma i ne te che presto

a la bu- ona memoria di Ruberto denari 200 quando ando in champo e perse la vita ↓

Roberto Strozzi was fatally wounded on 6 July 1495 in the

Battle of Taro while fighting as part of the Italian League led by Venice against

Charles VIII in 1495. Though he does not cite his source, Pompeo Litta describes the

gruesome death of Roberto Strozzi: 'Certamente il suo cadavere coperto di ferite,

fu

trovato in mezzo a' corpi morti de' nemici'; and for which see:

[Pompeo Litta,

'Famiglie celebri d’Italia', Vol. 4 (Milan 1837), Tav. IX.]

e la roba, e questa posisione ela la vende per denari 200 ela avea presta, la qual ↓

I am unable to tell whether a tear on the right-hand side of the manuscript has

resulted in the consequent loss of a letter. The word may be present in the folio

in its entirety or it might

indeed also be possible that Luisa had originally written 'quale'.

posisione ne vale denari 600 chon pati si mise a li chanto ch’el povero orfono ↓

The consequent loss of the letter 'o' can be

repaired here with certainty. Luisa's emotive reference is to her grandson Robertino

Strozzi, whose widowed mother Laudomia

Acciaiuoli had taken her dowry with her and abandoned the little boy upon her

remarriage after the death of Roberto Strozzi. As the children of remarried widows

were left to the care of paternal kin,

Luisa was given guardianship of the boy in 1498 and obliged to assume once more in

her old age the functions and role of a

mother. The wresting of these assets from the little boy, which Laudomia transmitted

to her new husband, and Robertino's

ensuing poverty, were the subject of various letters between Luisa and her sons in

1498. Luisa's transmission of property

to Robertino and her instructions regarding the investment in land on his behalf emphasises

the financial debacle that

Laudomia left behind her, and with which Luisa was obliged to contend in her old age.

la puo rischuotere e la lavora al presente u’lavorente si domanda Zan ↓

'Zan' for 'Gian'

Domenigho fozato; sichè salve questa mia letera per una testimonaza.

Ite che vo' dare a una puta naturale dela buona memoria di Ruberto ↓

Luisa's

reference to her bequest to a 'natural child' of Roberto Strozzi, and in the memory

of her dead son, resumes a lament of the widow from an earlier letter to Leona in

1509. In March of that year, Luisa recounted to Leona that the grandmother of Roberto’s

bastard children was

seeking to claim part of the investment she had made with her earnings at court. Luisa

Strozzi in Villabona to Leona Strozzi in Ferrara, 15 March 1509: Archivio di Stato,

Ferrara, Archivio Bentivoglio, Corrispondenza, Mazzo 3, 8-3, fol.

57r.

che anda in le suore chosta in tera nuova che si mura el munistero denari 25.

Ite che prestai zerti ↓

'zerti' for 'certi'

danari a Franzescho

↓

'Franzesco' for 'Francesco'

da

Bagniachavallo

↓

A town in the province of

Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna

quando ando

in ‘nugheria ↓

Hungary

chon’l chardinale e

otto perzento

↓

'perzento' for 'percento'

e voio solamente 5 perzento a ghua- dagnio e vi priegho mandiate per lui e li sia ristituiti quel più da 5 perzento.

Volte che novo quel pech[...]. ↓

The bottom right-hand corner of the folio has been torn and partially folded,

obscuring one to two words from the end of the line.

2 verso

In questo’ora è venuto el nostro Illustrissimo Signore Ducha ↓Alfonso

d'Este

e lo vo ire a vizitare

e li parlerò di questi danari che fazi sua Signoria i sia sodisffata, ↓

Luisa's access to the Duke underscores the

longevity of her proximity to the d'Este and the space to maneuver this afforded her.

e a Vostra

Magnificenza mi rachomando. Die 23 luio 1510.

Vostra Luisa Strozzi

in la Badia. ↓

Unfortunately the epistolary sources are unclear as to which ‘Badia’

located near Ferrara, or possibly Padua, Luisa here refers. In an early essay on the

Archivio Bentivoglio, Cecil Clough referred to the Strozzi

family farm in the Badia of Villabona, near Castelbaldo: a comune in the Province

of

Padua and located on the western side of the Adige River.

[Cecil H. Clough, ‘The

Archivio Bentivoglio in Ferrara’, 'Renaissance News', Vol. 18, No. 1 (1965), 12-19

(p. 15).]

Another possibility, however,

might be Badia Polesine in the Province of Rovigo in the Veneto region of north-eastern

Italy. In spite of the obscurity of the location,

it is likely, however, that it was the same ‘Badia’ to which Giovanfrancesco Strozzi

retired.

Magnifice et zenerose ↓

'zenerose' for 'generose'

tanqua

sorela onoran-da done Leona di Stro ↓

The remainder of the word, being the Strozzi name, has

not been written out in full in the original.

Ferarie. ↓

Ferrara