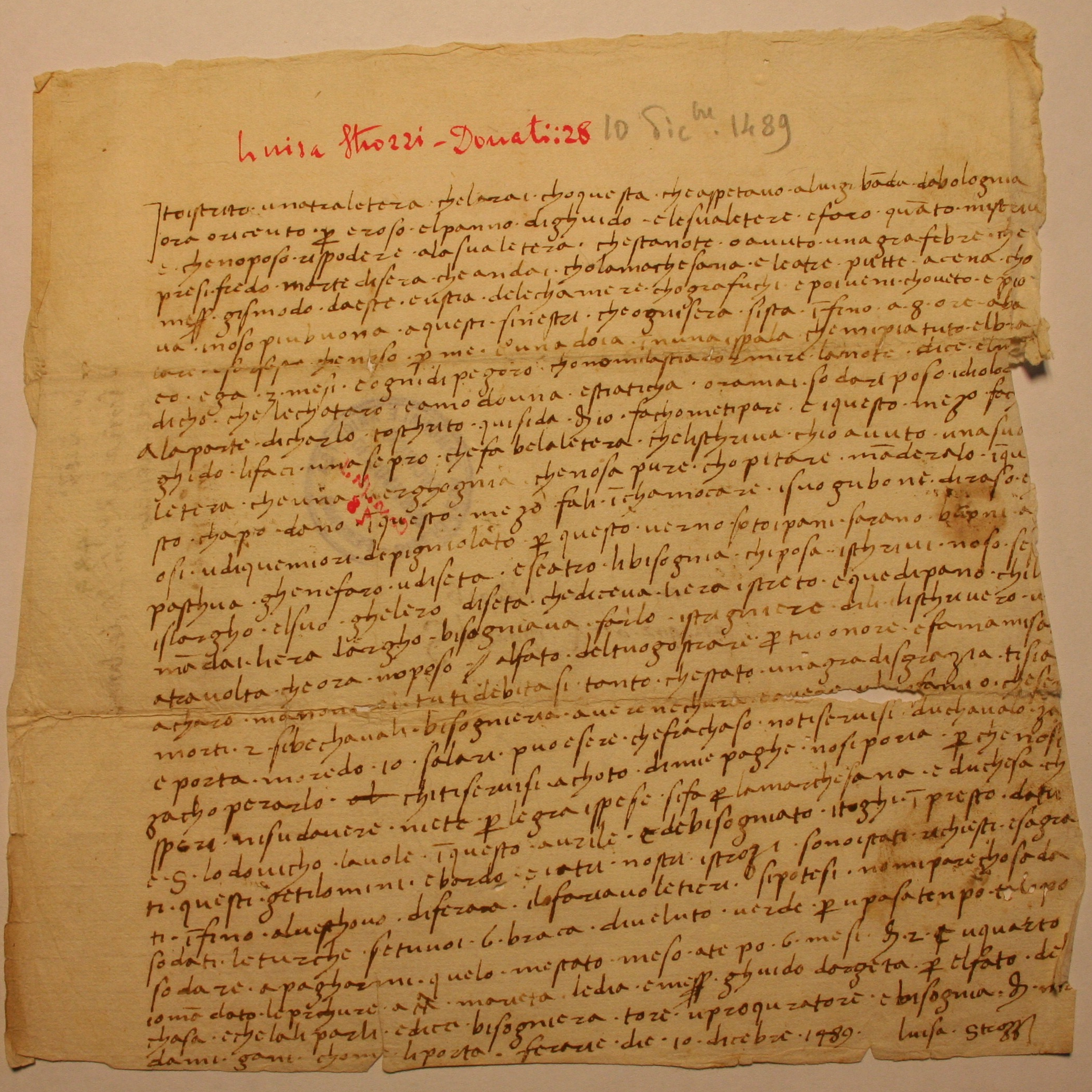

To Roberto Strozzi in La Badia, 10 December 1489

Archivio di Stato, Ferrara, Archivio Bentivoglio, Lettere Sciolte, Mazzo 1, fol. 28r-v

28 recto

I t’o iscrito un’atra letera che l’arai cho’ questa che aspetavo a Luigi Banda ↓I am unable to identify the carrier into whose

charge Luisa handed over her letter. In the absence of a central personalised postal

system,

Luisa entrusted her letters to carriers or messengers. These might have taken the

form of regular carriers or bearers, travelling friends,

relatives or personal servants. As Judith Bryce has recently shown to be the case

with Alessandra

Strozzi, Luisa may also have benefited from the couriers ('fanti') who serviced

businesses and banks, such as the Strozzi or Machiavelli banks in

Ferrara, and who would travel established routes.

[Judith Bryce, ‘Introduction', in Alessandra Macinghi Strozzi,

'Alessandra Macinghi Strozzi: Letters to Her Sons (1447-1470)', ed. and trans. by

Judith Bryce (Tempe: ACMRS, 2016), pp. 1-28 (p. 17).]

Luisa's correspondence

was sometimes carried in conjunction with other commodities and personal

goods, such as cloth, items of clothing, wax, flax, cheese, and other foodstuffs.

da bolognia.

↓

The town and commune of Bologna was an important junction of the roads and waterways

connecting Lombardy and the Romagna with

the Veneto and Tuscany. The Bentivoglio family established a long-lasting 'Signoria'

in Bologna in the fifteenth century.

It is likely that Luisa's spelling of Bologna as 'Bolognia' is phonetic and close

to her spoken language and

pronunciation of the city's name.

Ora o riceuto per è Roso ↓

Although the identity of the

person named here is obscure, Luisa's reference is to a private carrier or bearer.

el panno di

Ghuido e le sua letere

↓

The multiple hands and stages through

which Luisa's cloth and letters passed before they reached her at their final destination

sheds light on

the intricacies of postal arrangements in the period.

e farò quanto mi scriv-e che no' poso rispodere a la sua letera; che sta note o auuto una gra’ febre che

presi fredo morte di sera che andai cho’ la machesana ↓

Luisa's reference is to Isabella d'Este, aged fourteen years. Isabella

was the first of six children and the eldest daughter born to Duke Ercole I, d'Este,

Duke of Ferrara, and to the daughter of King Ferrante of Naples, Eleonora d'Aragona

(d. 1493). She was betrothed in 1480 to Francesco II Gonzaga (1466-1519), marchese

of

Mantua, and was married in 1490. In her role as marchesa of Mantua, Isabella was a

powerful consort wielding considerable cultural and political influence in Mantua

and

the region. Luisa's accompanying of the adolescent Isabella d'Este, along with 'the

other girls'

of the court, to dinner with the duke's brother sheds light on the Strozzi widow in

her role as governess to

Isabella and her younger sister, Beatrice. Luisa's appointment at court was at the

request of the Este Signoria and she served in the child-care role from 1480 until

1490.

e le atre putte

↓

Luisa's reference here is to 'the other girls' of the court.

a cena cho’

Messer ↓

A personal title used for knights and lawyers: the former

intended by Luisa in this instance.

Gismodo da Este

↓

Sigismondo d’Este (1433-1507) was the full brother of Ercole I

d'Este, Duke of Ferrara. Slightly younger than the Duke, Sigismondo and Ercole had

grown up together in Naples and remained close. Ercole relied on Sigismondo more than

anyone except his wife, Eleonora d'Aragona, whom incidentally he was deputed to

escort from Naples to their wedding in 1473. Following the death of Eleonora

d'Aragona in 1493, Sigismondo was charged with the governing of the state in the

absence of the duke.

[Thomas Tuohy, 'Herculean Ferrara: Ercole d’Este (1471-1505) and

the invention of a ducal capital' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p.

41.]

e uscia dele chamere cho’ gra’ fuchi e poi veni cho’ veto e pio-va. ↓

Tantalizing insights into Luisa’s integration into

Ferrarese court society emerge in this letter, revealing the close proximity of this

Florentine émigré widow to the ruling family which was very important for developing

new and creative strategies of personal and family survival in the hostland. This

is

observable in the long anecdote here in which Luisa, discharging her duty as Isabella

d'Este's governess, accompanied the young marchesa and the other children of the

court to dine at the residence of Sigismondo d’Este.

I no’ so' più

buona a questi finestri, che ogni sera si sta infino a 8 ore a ba-lare ↓

A description of court festivities is masterfully corralled in the body of the

letter to underscore Luisa’s inclusion in the network of the courtly milieu. Unable

to attend to her other letter-writing labours, Luisa reported that she had suffered

the symptoms of ‘a great fever’ over night, having caught her ‘death of cold’ upon

leaving Sigismondo’s palace, with its ‘rooms with great fires’ and stepping out ‘into

the wind and rain’ of the night. The cursory treatment of her dining companions

implies a well-established familiarity with this elite community; though the decorum

and obligations

of courtly society could be taxing. Luisa grumbles here to Roberto that,

weary of court festivities, she was ‘no longer able to practice these courtesies,

that every evening they dance up to eight hours’: an endless round of musical evenings

and banquets

her aging body and rheumatic ailments rendered difficult for her to partake in, and

indicated

by her poor health reported on below.

[...]

↓

The first main horizontal

fold of the letter renders a small fragment of the text in this section illegible.

che ne so per me

e una doia in una ispala che mi pia tuto el bra-co è ga 3 mesi e ogni dì pegoro cho no' mi lascia dormire la note. Dice el me-

dicho che le chataro. È a modonna ↓

Modena: a city in northern Italy,

southwest of Ferrara and in the region of the Emilia-Romagna. Dominion by the Estense

family began in the thirteenth century

and lasted until the beginning of the eighteenth century.

e stia ticha oramai so da riposo. Idio lo conforto.

↓

The edge of the manuscript has crumbled and, therefore, I surmise the word

'conforto' here.

A la parte di Charlo ↓

Carlo Strozzi's birth

and death dates are unknown. However, of Luisa's sons who remain to any degree

visible to the historian’s eye, no less than two embarked upon military careers.

Carlo had initially commenced training to become a priest. However, a position in

the

Church appears to have fallen away and he pursued a career as a soldier, serving as

a

mercenary captain in the Venetian republic until 1509 when he was employed by the

Estensi in the war of the League of Cambrai. Throughout Luisa's widowhood, Carlo's

litigious and

quarrelsome nature was the source of considerable financial and emotional distress

suffered by the

widow. Indeed, mother and son were often pitted against one another in protracted

litigation over property claims

and Luisa's right to lifetime use over property that Carlo Strozzi regarded as his

own.

t’o schrito qui si da denari

10;

↓

The basis of the currency system in central and northern Italy

during the Renaissance period was 12 denari = 1 soldo.

fa chome ti pare e i'

questo mezo fa[...]

↓

The centre right-hand side of the manuscript has been torn off and lost, eliminating

one to two words from the end of the line, and, therefore, the beginning of the first

word of the subsequent line.

ghido li faci una [sepro] che fa bela letera che li schriva ch’i o auuto una suo

letera ch'è una verghognia che no sa pure chopitare. ↓

Luisa's correspondence is

interspersed with direct references to her letter-writing. Moreover, her comment here

points explicitly to the autograph status of her letters. Although there is no

concrete information regarding the development of Luisa's literacy skills, it is most

likely that their acquisition took place within her natal home in Florence. As Judith

Bryce has recently argued in the case of Alessandra Strozzi, Luisa's writing ability

was also considerably developed as a result of the exilic

circumstances in which she found herself, and in carrying our her perceived role in

relation to

her exiled sons.

[Bryce, ‘Introduction’, pp. 5-6.]

Differently from her distant Strozzi kinswoman, however,

Luisa's ability to write was also developed and enhanced away from her natal city

and kin, and under the circumstances of

migration and widowhood.

Manderalo in que-

sto chapodano. In questo mezo fali inchamocare i suo gubone di raso e [...] ↓

The large tear

on the right-hand side of the manuscript eliminates the word here, which continues

onto the subsequent line,

and for which I am unable to supply even a conjectural transcription.

[...]osi u' di que miori de pigniolato per questo verno soto i pani sarano buoni. A

paschua [ghe] ne farò u’ di seta e se atro li bisognia chi posa ischrivi. ↓

Luisa frequently

pawned precious material goods belonging both to her and her sons, including fine

fabrics and clothing, in order to obtain cash.

No' so s'è [...]

↓

The tear also eliminates the word here, which continues onto the subsequent line,

and for which I am unable to supply even a conjectural transcription.

[is]largho el suo ghelero di seta che diceva li era istreto e que’ di pano ch’i li

mandai li era largho. Bisogniava farlo istrigniere. ↓

Clothing, linens, cloth, and the mending or altering and dispatching

of these items saturate Luisa's correspondence. Here, the Strozzi mother's punctilious

presiding over the construction and alteration

of her son's garments, including the problem of their correct fit, can be viewed as

Luisa's maternal obligation to care

for the physical bodies and appearance of her sons, even throughout their adulthood.

This point is also made by Bryce regarding

Alessandra Strozzi and the 'pervasive presence of the material world' in her letters

as evidence of the maternal care of

the filial physical body.

[ Bryce, ‘Introduction', p. 19.]

Dili i li schriverò u

↓

It is possible that the tear from the centre of the folio has eliminated the letter

'n' here, and which would, therefore,

have formed the word 'un'.

atra volta che ora no' poso.

Al fato del tuo gostrare per tuo onore e fama mi sa[r]- ↓

The tear has eliminated one to two letters

of the word. I have supplied the most plausible missing letter.

a charo, ma non [arai] ↓

A tear in the fold has removed the word here and I have supplied

only a conjectural transcription.

tu ti debitasi tanto ch'è stato una gra’ disgrazia.

↓

The use of

Luisa's court appointment by Roberto to assimilate himself into courtly society led

his mother to snappily scold him in

her letter for his extravagant jousting expenses, which amounted to a ‘huge

disgrace’. Presumably Luisa was left to use her position to resolve the debt with

the court.

Ti sia

morti 2 [si be'] chavali. Bisognieria averene chura e avere [...] ↓

A hole in the manuscript has

eliminated the entire word.

famio che se[...]

↓

It is possible that one to three letters

have been eliminated here by the tear in the folio.

e porta [moredo] 10 salari puo esere che fra chaso no’ ti servisi du chavalo za[...]- ↓

One to two letters

have been eliminated in this section of the letter by the tear in the folio. From

the opening letters of the subsequent line, it is

plausible that the missing letter is 'n', thereby forming 'zanza' for 'senza'.

za choperarlo, al, chi ti servisi a choto di mie paghe no' si poria ↓

As a permanent salaried member of the Este court,

employed in the capacity of governess to Isabella and Beatrice d'Este, Luisa occupied

a desirable condition: the security of life at court, which could neutralize the

vulnerability and impoverishment of widowhood. Moreover, for a widow in a foreign

hostland and attached to exiled menfolk, a court position that was independent from

the disgraced status of her deceased husband could provided practical financial consequences

for the support of the remaining members of her family. Luisa's notification to

Roberto suggests, however, that the opportunities to generate income could be

exploited by her adult sons for personal financial gain.

perchè no’ si

speri nisu’ d’avere niete per le gra’ ispese si fa per la marchesana ↓

Isabella d'Este

e duchesa

↓

The reference

is to Isabella's younger sister, Beatrice (1475-1497), betrothed to Lodovico Sforza,

Duke of Bari.

ch-e Signore Lodovicho la vole in questo avrile ↓

Luisa's explanation

to Roberto that she would be unable to request money from the court, presumably to

funnel it his way, is noteworthy. It is plausible that the reason she offers is

concerned with the considerable expenses incurred by the court in amassing the large

dowries required for the marriages of the two Este princesses. Isabella d'Este was

betrothed to Francesco Gonzaga (1466-1519), marquis of the state of Mantua, and her

sister Beatrice to Lodovico Sforza ("il Moro") (1451-1508), Duke

of Bari. The official nuptials were to have taken place in 1490 in a double wedding,

but Lodovico postponed the wedding more than once, and it may be this to which Luisa

here refers in her statement that Lodovico 'want(ed) Beatrice in April'. Isabella

and

Francesco were married three months after this letter of Luisa in February 1490,

while Beatrice and Lodovico were married in January 1491.

e de’ bisogniato i

toghi in presto da tu-ti questi getilomini; e Bardo ↓

Bardo Strozzi, the grandson of Palla Strozzi,

was the son of Lorenzo di Palla and Alessandra de' Bardi. Marietta Strozzi, who also

appears in the letter below, was Bardo's sister. Bardo settled in Ferrara and married

Diana Riccardi, the daughter of a noble Abruzzese family.

[Pompeo Litta, 'Famiglie

celebri d’Italia', Vol. 4 (Milan 1837), Tav. IX.]

This branch of the Strozzi and their

descendants remained in Ferrara. Though Bardo demonstrated a fervent patriotism for

the Strozzi's ancestral city where he was brought up, he did not ever return there

permanently. Presumably his decision had to do with his favourable position at

the Ferrarese court. It is evident from her correspondence that Luisa was in contact

with Bardo, who appears to have been a trusted confidant and adviser of the widow.

e i atri

nostri Strozi sono istati richiesti e sagra-ti infino al veschovo di Ferara.. ↓

Because of the projected wedding of Lodovico il Moro and Beatrice

d'Este, it is possible that Luisa's reference here in her letter is to a request of

the duke for the presence of Bardo and all the Strozzi of Ferrara. According to

Luisa, the request invested the Strozzi with a higher dignity, equal to that of the

bishop of

Ferrara, the Franciscan Bartolomeo della Rovere (d. 1494).

Il faria voletieri si potesi. No’ mi pare

chosa da sodati le turche.

Se tu voi 6 braca di veluto verde per u’ pasatenpo, te lo po-

so dare a pagharmi quelo m'è stato meso a tepo 6 mesi: denari 2 e u' quarto.

Comandato le prochure a Madonna Marieta ↓

Marietta Strozzi was the niece of Luisa Strozzi: the

daughter of Lorenzo di Palla Strozzi, the brother of Luisa's husband, Giovanfrancesco

Strozzi. Marietta had lived as a ward with Giovanfrancesco following the death of

her

parents. Marietta's marriage to Teofilo Calcagnini, a courtier and close associate

of

Duke Borso d'Este, provided Luisa with an important and strategic familial connection

at the Este court.

le dia e messer Ghuido d’Argeta

↓

A messenger used by Luisa.

per el fato de[la]

↓

A fold and partial tear in

the folio obscures the last two letters. As such, I have supplied the particular spelling

of 'della' ('dela') utilised consistently by Luisa elsewhere in her correspondence.

chasa e ch'el a li parli e dice bisognierà tore u’ proquratore, e bisognia denari [...]. ↓

A fold

and partial tear in the folio obscures the last two or, possibly, three letters of

the last word of the line.

dami gani chome li porta. Ferarie, ↓

Following her marriage to Giovanfrancesco Strozzi in Verona in 1449,

aged fifteen, Luisa left her native Florence for Padua. She appears to have lived

for

some time in the Paduan residence of her father-in-law Palla Strozzi, along with her

infant children. It is probable that the establishment of Giovanfrancesco’s household

in Ferrara in 1453 brought the nineteen-year-old Luisa to the court city, where she

remained until her death in 1510.

die 10 dicebre 1489. Luisa Strozzi

28 verso

Spetabili viro Ruberto ↓ The broadening of the Medici regime's expulsion decrees in late

1458 against the original rebels of 1434 to include their male descendants, placed

Roberto Strozzi under the formal ban of exile from Florence for twenty-five years.

Born in Ferrara in 1465, Roberto Strozzi was educated as a page in the court of

Ercole d’Este I where, as was customary within the courtly environment, he could

cultivate military skills together with more peaceabale achievements. When Roberto

was recruited into the

military service of Venice is unclear, but he served the Republic until his death

at

thirty as a mercenary captain in the battle of Taro, fighting as part of the Italian

League led by Venice against Charles VIII in 1495. Though he does not cite his

sources, Pompeo Litta describes the gruesome death of Roberto Strozzi on 6 July 1495:

'Certamente il suo cadavere coperto di ferite, fu trovato in mezzo a' corpi morti

de'

nemici'; and for which see, Pompeo Litta, 'Famiglie celebri d’Italia', Vol. 4 (Milan

1837), Tav. IX.

Strozzi in la Badia ↓

Unfortunately the

epistolary sources are unclear as to which ‘Badia’ located near Ferrara Luisa here

refers. In an early essay, Cecil Clough referred to the Strozzi family farm in the

Badia of Villabona, near Castelbaldo: a comune in the Province of Padua and located

on the western side of the Adige River.

[Cecil H. Clough, ‘The Archivio

Bentivoglio in Ferrara’, 'Renaissance News', Vol. 18, No. 1 (1965), 12-19 (p. 15).

]

An alternate possibility to that proposed by Clough might in fact be Badia

Polesine in the Province of Rovigo in the Veneto region of north-eastern Italy. It

is

likely that it was the same ‘Badia’ to which Giovanfrancesco Strozzi

retired; though which of the two possibilities this in fact was remains obscure.

10 dicembris 1484

Scrive a Roberto Madona Luisa de danari e de veludo. ↓

This section of the manuscript is written in another

contemporary hand, and which belongs to Alessandro Strozzi, Luisa's son:

interestingly, not the intended recipient of the letter. The short annotation

provides an example of the epistolary summaries Alessandro composed on the backs of

many of his mother's letters. From these annotations, it would appear that Alessandro

preserved many of them. The preservation of more than two hundred of her letters

within the family collection is largely a measure of the perceived importance by

Alessandro, who was a male head of household, of Luisa’s correspondence as

patrimonial records connected to land, patterns of inheritance and family. However,

drawing from James Daybell's analysis of epistolary annotations in his recent study

of British correspondence, Alessandro's summaries might also be seen as a biographical

act of recording and classifying his mother's role and activities in the Strozzi's

family history after the initial function of her letters were exhausted.

[James Daybell,

'Gendered Archival Practices and the Future Lives of Letters', in James Daybell and

Andrew Gordon (eds).,

'Cultures of Correspondence in Early Modern Britain' (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2016), pp.

210-36 (pp.218 and 226).]